A Gary Revel Investigative News Web Site

New York, New York USA

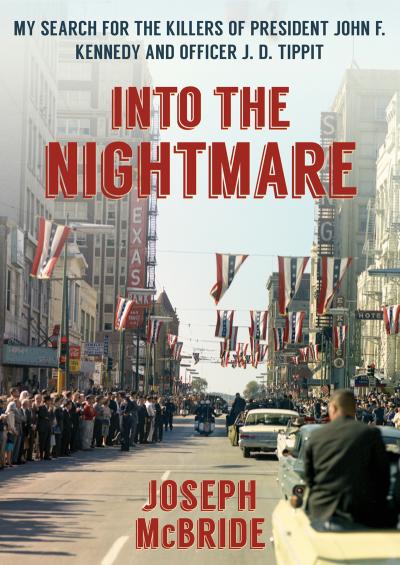

INTERVIEW OF JOSEPH McBRIDE

| Tweet |

#1. In your book Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J. D. Tippit (2013), you discuss how Lee Harvey Oswald was tried in the media by officials led by Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade who spoke of his guilt in definite terms. Can you expound a bit on the coverage that Oswald received after his arrest?

McBRIDE: Trial-by-television unfortunately is now the norm in our society. Suspects spotlighted by the media are assumed to be guilty before proven innocent. The Constitution is regarded as “quaint,” to borrow the infamous word of George W. Bush’s stoogeish Attorney General Alberto Gonzales. I first saw this phenomenon in operation with the high-tech lynching of Lee Harvey Oswald (I was sixteen at the time; it had been going on well before that in the media-manipulating hands of Joe McCarthy and others). From day one of the assassination weekend in November 1963, the TV networks and most of the print media assured us that Oswald was the lone killer of President Kennedy. On the other hand, I was a skeptic from day one, because (1) I had heard the early radio reports of shots from the front and listened as they were magically transformed into shots only from behind, between 12:40 and 1 p.m.; and (2) I believed Oswald’s protestations of innocence on live television that night. The notion promoted by government officials and the media that he shot the President to gain notoriety is hard to reconcile with his repeated statements that he didn’t do it.

John F. Kennedy at a Milwaukee rally, April 3, 1960

Photo by Joseph McBride, © 1999

Evidently many other Americans were also thinking for themselves, because they generally didn’t buy this media circus, as public opinion polls have shown from that November until today. About three-fourths of Americans over the years have consistently rejected the lone-gunman theory put forth by the Warren Commission. Public officials had been feeding the media that script from the early afternoon of November 22 onward; it was a scenario that had been quickly decided upon by the White House Situation Room, J. Edgar Hoover, et al. Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade was one of the prime offenders. For example, Wade declared on November 24, after Oswald was killed in the Dallas police station, that he was the lone assassin, “without any doubt . . . and to a moral certainty.”

#2. Jack Ruby did not spontaneously appear in the Dallas Police Department basement and shoot Oswald, as the story often is superficially presented. Can you speak a bit on how Ruby had been stalking Lee Oswald nearly the whole time he was held in custody?

McBRIDE: It later emerged that Ruby was in the lineup room at the Dallas police headquarters when Oswald was brought out around midnight Friday for his live TV showing. That was arranged by Henry Wade (as Wade told me) to demonstrate that the prisoner wasn’t being roughed up (much) in police custody. But that ploy backfired when the media began asking Oswald questions, which Wade told me was not his intention in setting up the event. Oswald responded succinctly and with remarkable dignity that he was innocent and had not even been officially charged with killing President Kennedy, only with shooting a policeman (Officer J. D. Tippit). Dallas Police Detective James Leavelle, who participated in Oswald’s interrogation, confirmed to me that Oswald was telling the truth, although the media seemed to assume he was lying when he said that he had not been charged with killing the President. Leavelle said, “He’d been told it, but see, he hadn’t been charged with it, so he answered it truthfully. He knew he was a suspect, but he hadn’t been charged with it.’

Jack Ruby was not close enough in the crowded lineup room of the police station to get off a clean shot, although he was carrying a pistol. Ruby had been much in evidence around the station from that afternoon onward, making himself useful to the press and police to help justify his presence; Ruby was also present when Wade gave his error-filled press conference shortly after Oswald’s public showing. Ruby corrected Wade about a fine point of Cuban exile politics. Ruby evidently was let into the police basement to kill Oswald on Sunday morning. That inside job was a somewhat desperate move with time running out, since it had to be done on live television while Oswald was in the process of being transferred to the more secure county jail. I believe the original plan was to have Oswald eliminated, along with Kennedy and Tippit, all in the first hour on Friday, but Oswald miraculously escaped alive and remained so for a brief time.

#3. Is it true that Oswald was never charged with the murder of JFK, but only with the murder of Officer Tippit? Further, is it true that Oswald received no legal representation the entire time he was held in custody, and none of his statements was recorded?

McBRIDE: Oswald actually was charged with the murders of both Kennedy and Tippit, but he was only arraigned for the murder of Tippit, as an FBI document demonstrates. When I told Leavelle, the lead detective in the Tippit case, about the FBI report, Leavelle replied that “he was arraigned early on the Tippit shooting. But I was thinking that we also arraigned him somewhere down the line on the shooting of the president. But I wouldn’t swear to that offhand.” Leavelle explained that Captain Will Fritz, the head of homicide, had told him, “Well, go ahead and make a tight case on [Oswald for the Tippit killing] in case we have trouble making this one on the presidential shooting.” Many people have assumed, then and now, that if Oswald was accused of killing Tippit, he must have killed Kennedy, a piece of backward logic that would make Lewis Carroll envious. Oswald, at his brief press conference, made a poignant plea for “someone to come forward, uh, to give me, uh, legal assistance.” The attorney he preferred, John Abt of New York, who was known for representing leftists, shamefully ducked the request that weekend. Enough people around the country were alarmed that Oswald had no legal representation that the president of the Dallas County Bar Association, H. Louis Nichols, visited him in his cell on Saturday to see if he wanted a local attorney appointed, but Oswald said he wanted Abt or a member of the American Civil Liberties Union. It’s part of the tragedy of the case that Oswald died without ever having representation. His rights might have been protected if he had had a lawyer from the first day.

Oswald’s statements under interrogation were not tape-recorded, as far as we know. All we have are secondhand reports by the police and other interrogators and some written notes purporting to tell what he said. None of these records can be taken at face value. So we don’t really know what Oswald said under interrogation. Researcher Mae Brussell did compile a useful list of the statements Oswald made to the media (including some as he was led through the halls of the police station) and the statements he was alleged to have made under interrogation. That list, first published in The People’s Almanac #2 in 1978, under the title “The Last Words of Lee Harvey Oswald,” can be found online.

#4. Can you speak a bit about what Roger Craig had to say about seeing Oswald in custody, and if his account was later vindicated?

McBRIDE: Roger Craig was a Dallas County deputy sheriff with a distinguished service record. In his 1971 manuscript on the case, When They Kill a President, Craig wrote that he saw “a white male in his twenties running down the grassy knoll from the direction of the Texas School Book Depository Building” and entering a light green Rambler station wagon driven by a Latin man on Elm Street at 12:40 p.m., ten minutes after the assassination (there is photographic evidence of a station wagon on Elm Street at just the time Craig reported, as established by the clock on the roof of the building). Craig was “convinced” that the man entering the car was Oswald. While Oswald was being interrogated at 4:30 that day, Craig identified him to Captain Fritz, who, Craig wrote, “told Oswald, ‘This man (pointing to me) saw you leave.’ At which time the suspect replied, ‘I told you people I did.’ Fritz, apparently trying to console Oswald, said, ‘Take it easy, son -- we’re just trying to find out what happened.’ Fritz then said, ‘What about the car?’ Oswald replied, leaning forward on Fritz’ desk, ‘That station wagon belongs to Mrs. [Ruth] Paine [his wife’s CIA-connected handler] -- don’t try to drag her into this.’ Sitting back in his chair, Oswald said very disgustedly and very low, ‘Everybody will know who I am now.’” Craig stuck to his story and was hounded to his death in 1975. He is one of the heroes of the case, a rare example of a lawman who actually tried to do his job in investigating who killed President Kennedy.

Buy the Book

#5. You report that Henry Wade stated that he might not only not have won a trial charging Oswald with JFK's murder, but he may incredibly not have even chosen to file a case. Can you speak a bit on your interview with Henry Wade?

McBRIDE: Wade expressed many doubts about the case in his lengthy testimony before the Warren Commission in 1964. He testified that he told Police Chief Jesse Curry on the morning of November 23 that “there may not be a place in the United States you can try it with all the publicity you are getting.” He said he “felt like nearly it was a hopeless case” after Curry, disregarding his warnings not to have the department broadcast so much evidence, went on national TV that afternoon to discuss FBI evidence supposedly linking Oswald to the assassination rifle. Wade discussed at length before the commission how difficult it would have been to get a conviction of Oswald after the police had so badly tainted the potential jury pool by parading and discussing the supposed evidence in public, as was their usual practice but in this case brought them a huge worldwide audience.

Wade deplored that practice as counterproductive, although he was also guilty of doing so that weekend. Wade admitted that in his own November 24 press conference, after Oswald was killed, “I was a little inaccurate in one or two things but it was because of the communications with the police. . . . I ran through just what I knew, which was probably was worse than nothing.” Although his sometimes convoluted and cryptic testimony can be subjected to various interpretations, in my reading of it, the initial concerns he testified to having before he was briefed by the police about their evidence (“I wasn’t sure I was going to take a complaint”) resurfaced later and continued to plague him. He told the commission, “I will say Captain Fritz is about as good a man at solving a crime as I ever saw, to find out who did it, but he is poorest in the getting evidence that I know, and I am more interested in getting evidence, and there is where our major conflict comes in."

Wade, with all his flaws, was a cagey and smart and slippery prosecutor. I grilled him carefully in his office in 1992, after he had left his long tenure in office but while he was still practicing law in Dallas. I led up to the pointed questions with some casual ones and then let loose with a series of tough questions that elicited some remarkably candid responses (such as “I probably made a lot of mistakes”), along with some of his trademark evasion and some apparent ignorance. He actually may have been ill-informed on some questions -- he was known for playing it fast and loose with the facts of cases -- but he did make some important revelations in our interview. Wade told me he didn’t hear Oswald’s name until about 3 p.m. on November 22, but he said cryptically, “Somebody reported to me that the police already knew who he was, and they were looking for him.”

This corroborated one of the main findings of my research for Into the Nightmare, that J. D. Tippit and another officer (probably William D. Mentzel, who, unlike Tippit, was assigned to the district where the shooting took place) had been assigned to hunt down Oswald in Oak Cliff (where he lived) in the immediate aftermath of the assassination. The other officer involved in the hunt admitted this to Tippit’s widow, Marie, who told her father-in-law, Edgar Lee Tippit, who revealed it to me. This scenario fits with Officer Tippit’s increasingly frantic chasing around Oak Cliff before he was shot and with Mentzel’s erratic movements and changing accounts of what he was doing in that period. I believe they were supposed to either capture or kill Oswald. That they were sent to do so before Oswald’s identity officially was known to the Dallas Police Department (although there is strong evidence the police had been tracking Oswald before November 22 and/or using him as an informant) is proof that Tippit, Menzel, and the department they worked for were involved in a conspiracy to frame Oswald and quite possibly to eliminate him that first day.

Wade, a former FBI agent, also told me that Oswald had spoken with the FBI Special Agent James P. Hosty, Jr., “Within a day or two [before the assassination], I don’t know exactly.” This was a remarkable revelation, if it is true. The FBI admitted that Oswald had come to its Dallas office with a note, said to have been threatening, on or about November 12. But the Dallas Morning News reported on the morning of November 24 -- in its Sunday edition published while Oswald was still alive -- that he had spoken with the FBI on November 16. That account was long forgotten until I dug it out of the newspaper microfilm. But if Wade is correct, and Oswald was in touch with the FBI even more closely before November 22, it buttresses the abundant evidence that Oswald was an FBI informant. I believe he thought he was tracking the plot against Kennedy for the U.S. government and wound up being unwittingly used as a scapegoat in that plot.

#6. Your work calls attention to the documentary The Thin Blue Line (1988) and highlights JFK and Tippit players Henry Wade and Gus Rose. Can you please elaborate a bit on their roles as shown in the documentary, and how it reflects on the JFK and Tippit cases?

McBRIDE: Errol Morris’s great documentary film was responsible for freeing Randall Dale Adams from prison on the trumped-up charge that he had killed Dallas Police Officer Robert Wood in 1976. That charge had been brought with fraudulent and coerced evidence by Henry Wade’s office. Morris managed to get a virtual confession on audiotape from the actual killer, David Harris. The film threw a spotlight on the laxity and corruption endemic in Wade’s office. Much has been written since then about how Wade and his deputy district attorneys routinely charged and convicted innocent suspects, some of capital crimes. This, in retrospect, sheds light on how they railroaded Oswald and, despite all the weaknesses in the case, planned to have him executed, on fabricated charges.

Gus Rose, who was one of the detectives involved in that charade involving Oswald, is interviewed in The Thin Blue Line. Adams tells Morris that Rose gave him the third degree to make him confess, threatening him with a gun; Rose is then seen blithely lying about what he did to Adams. I am a great admirer in general of the work of Morris, who is an old friend of mine from our days together in the Wisconsin Film Society at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Morris worked as a private investigator and has performed remarkable feats in getting a wide range of people (including public officials) to confess their crimes and other antisocial behavior on camera. I think The Thin Blue Line echoes the Tippit case in many ways, including visually, depicting the murder of a Dallas police officer on a quiet city street and exposing the railroading of an innocent man for the crime. It’s remarkable that in both cases the Dallas police and the DA’s office preferred to pin the blame on the wrong men rather than catching the actual killers of their brother policemen.

Morris, unfortunately, more recently has made some videos ridiculing conspiracy theories about the Kennedy assassination. These shoddy pieces of lone-nut propaganda are unlike his better work in such murder cases as those of Randall Adams and Dr. Jeffrey MacDonald. Morris’s 2012 book, A Wilderness of Error: The Trials of Jeffrey MacDonald, proves, to my satisfaction, that MacDonald is innocent of killing his pregnant wife and two daughters and points the finger convincingly at the actual culprits who were allowed to elude justice in the 1970 murders.

#7. When Officer Tippit was killed and Lee Oswald was charged with the crime, it seems any chance he had of fair treatment was gone. Does Tippit's death seem to have been improvised, since Oswald may have lived longer than a plan had called for? Where did that plan possibly go amiss?

McBRIDE: Since Tippit and probably his fellow officer Mentzel were hunting down Oswald, the plan may have been for one of them to shoot Oswald on the street and make it look like a gun duel. The public then would have been encouraged to think that Oswald had tried to kill a policeman after killing Kennedy, and the officer who killed Oswald would have been set up as a national hero. Obviously something went wrong. They didn’t find Oswald. Something even more complex occurred at that location.

Oswald, I believe, was not at the scene of the Tippit murder, despite the claims of a number of witnesses. Most of them identified him at dubious lineups, at later dates, or under duress. Several other people identified a short, stocky man as the shooter, said two men were involved, or claimed that the killer had escaped in a car, not on foot. Two said another police car was at the scene, and a witness who came out of her adjacent house upon hearing the shots said policemen were already present, even though the official account is that no other policeman besides Tippit was there for more than ten minutes after she heard the shots. The shootout between Tippit and Oswald that may have been planned didn’t take place.

So the backup plan, possibly Plan B but also possibly improvised, was to eliminate Oswald in the nearby Texas Theatre. He may already have been there at the time Tippit was shot or soon thereafter, not arriving considerably later as the official report would indicate. But hordes of policemen flooded the area shortly after it was reported that a policeman was shot, as is usually the case in such shootings. This conveniently drew policemen away from investigating the assassination downtown, and more critically it drew them into Oswald’s presence. According to official records, one man was arrested in the balcony of the theater. And another man was seen being taken out the back door under arrest. We don’t know who those men were, although the theory that there were two Oswalds (see John Armstrong’s 2003 book Harvey and Lee: How the CIA Framed Oswald) might provide at least a partial answer. The Oswald brought out the front door under arrest had the presence of mind to keep shouting, “I am not resisting arrest!” in front of civilian witnesses, so despite a mob of angry policemen and some Dallas citizens in a lynching mood, he survived to be taken downtown under arrest in a police car.

#8. Can you compare what witness and ballistic evidence indicates most likely happened to Tippit, as compared to what the legend states?

McBRIDE: If you read the Warren Report carefully, it shows that the Warren Commission was forced to rely entirely on the ballistics evidence to try to pin the Tippit shooting on Oswald, since its supposed star witness, Helen Markham, was hysterical and for the most part wildly unreliable. The problem was that the ballistics evidence in the Tippit case -- part of what Oswald meant when he told his brother Robert, “Don’t believe all this so-called evidence” -- was an utter mess. The cartridges produced into evidence were of two different makes. They supposedly were found in the grass and bushes later that afternoon, considerably after policemen saw other cartridges in the street at the crime scene. The cartridges from the street vanished. The ones entered into evidence are bogus. None of the four bullets allegedly recovered from Tippit’s body could be linked to the revolver allegedly taken from Oswald at the theater, partly because the slugs were too mutilated. Furthermore, some witnesses, including policemen, who reported from Oak Cliff that afternoon indicated that an automatic was involved in the shooting, not a revolver, suggesting to some researchers that the problems with the ballistics evidence resulted from a wholesale switching of ammunition in an attempt to implicate Oswald. In summary, the ballistics evidence actually tends to exonerate Oswald. When I asked Detective Leavelle about the discrepancies between the bullets and the cartridges entered into evidence in the Tippit case, Leavelle admitted, “Well, I don’t know that it’s identified that closely, if you want to know the truth about it. Because we had a little problem with the ballistics on that. And I’m not at all certain.”

The other physical evidence is also confused and contradictory, and the eyewitness evidence is so contradictory that it seems as though there were two sets of witnesses. That may actually have been the case. Researcher Jerry Rose theorized that Jack Ruby had set up a number of phony witnesses to implicate Oswald, and indeed a remarkable number of the so-called witnesses were involved with Ruby. Perhaps the single most significant piece of exonerating evidence, however, is the fact that the housekeeper of Oswald’s rooming house, Earlene Roberts, saw him waiting outside, as if for a ride or a bus, at around 1:04 p.m., and Tippit was killed at 1:08 or 1:09 nine-tenths of a mile away. Oswald could not have walked there in that time, and no one reported seeing him either walking or being driven to the scene of that crime.

#9. When we look at the legacy of Henry Wade and his record of convictions, how has his reputation stood the test of time?

McBRIDE: Wade’s record as DA from 1951 to 1987 is abysmal and shameful. The current Dallas County DA, Craig Watkins, has helped free thirty-three people falsely convicted by Wade and his office. Watkins has been investigating about five hundred suspicious cases in which there was reason to suspect wrongful conviction by Wade’s office and there is DNA evidence still available to test. Ironically, much of that evidence that has been freeing innocent people was preserved by Wade himself. His regime was a terrible time of injustice in Dallas, and Watkins has been trying to make up for it. If only he would reopen the murder cases of Kennedy and Tippit.

#10. After all your years of extensive interviews and exhaustive research, can you please share the hypothesis you have formed on what most likely happened to J. D. Tippit on 11/22/63 (and any other thoughts that may come to mind)?

McBRIDE: Officer Tippit was part of the conspiracy that day, at least to capture or silence the scapegoat even before he was officially known to the Dallas Police Department. The official story is that the police didn’t know Oswald’s true identity until after he was taken downtown to the police station after being arrested at 1:51 p.m. But Tippit was looking for Oswald as early as 12:45, if not before. He may have been thinking he was supposed to eliminate Oswald. And Tippit may have had other involvement in the conspiracy. He moved in a milieu of rightwing extremists, criminals, and highly corrupt law enforcement personnel. He would have been a prime candidate for recruitment into the plot. He was unstable, suffering from World War II-induced PTSD, had killed a man on duty, and was an excellent shot. He was under financial stress but came into money shortly before the assassination. He was also having problems with his marriage and had a mistress, Johnnie Maxie Witherspoon, who discovered she was pregnant right around the time of the assassination.

Some have theorized Tippit was actually shot by his mistress’s jealous husband or even by his mistress. I interviewed her and studied their movements and histories carefully and don’t believe they were involved in his death. That story has been floated as a fallback position to distract people from the more direct involvement(s) of Tippit in the assassination conspiracy. I am not the first writer to study whether Tippit might have been the Grassy Knoll shooter in Dealey Plaza known to researchers as “Badge Man,” the name given to a man in a Dallas Police Department uniform who was photographed firing some kind of a hand gun at Kennedy from the right front and side. The features of “Badge Man” bear a remarkable resemblance to Tippit’s distinctive hairline and other facial features. But this possibility has to be balanced with Tippit’s widow’s claim that he was home having lunch with her until soon before the assassination and another story that he was out of his car on police business in suburban Oak Cliff at 12:17 (the assassination occurred downtown at 12:30). Even though there are numerous problems with both of those stories, they can’t as yet be entirely discounted.

So I believe Tippit was marked for elimination on East Tenth Street in Oak Cliff, lured into a trap that probably involved another member of the Dallas Police Department (Harry Olsen) and a young hoodlum (Darrell Wayne “Dago” Garner) tied closely with Jack Ruby. Ruby himself may also have been at the scene. The movements of these three men were highly suspicious, and the accounts of some witnesses show that at least two men and probably another police car were involved in the incident, as well as possibly other policemen.

Why Tippit was lured into this trap is the big question. Was it simply a cynical, calculated move to draw other policemen into Oak Cliff to eliminate Oswald? Or was it a trap to get rid of Tippit because he had been involved in the plot, even perhaps in the shooting of Kennedy? It would have been a neat plan indeed to have both a shooter and a scapegoat eliminated along with Kennedy within an hour. Since we now know Tippit believed he was supposed to hunt down Oswald, was that part of a trap to lure him into a gunfight with Oswald to make all this seem legitimate?

We don’t know the whole story. We may learn more later. We may never know everything about what happened to Tippit. But thanks to my research and that of a few other dedicated researchers over the years (including Penn Jones, Gary Murr, Larry Ray Harris, Greg Lowrey, and Bill Pulte), we now know a lot more than the Warren Commission would have had us believe. Tippit was not an heroic cop who sacrificed his life for his country. He was part of the plot that also eliminated both Kennedy and Oswald. Tippit’s murder has drawn little public attention over the years. That suits the official story well, because when you look closely into the Tippit killing, as I did for more than thirty years in researching and writing Into the Nightmare, it proves to be integral to the story of the presidential assassination and its coverup. As the late Warren Commission assistant counsel David W. Belin wrote, though for a different reason, “The Rosetta Stone to the solution of President Kennedy’s murder is the murder of Officer J. D. Tippit.”

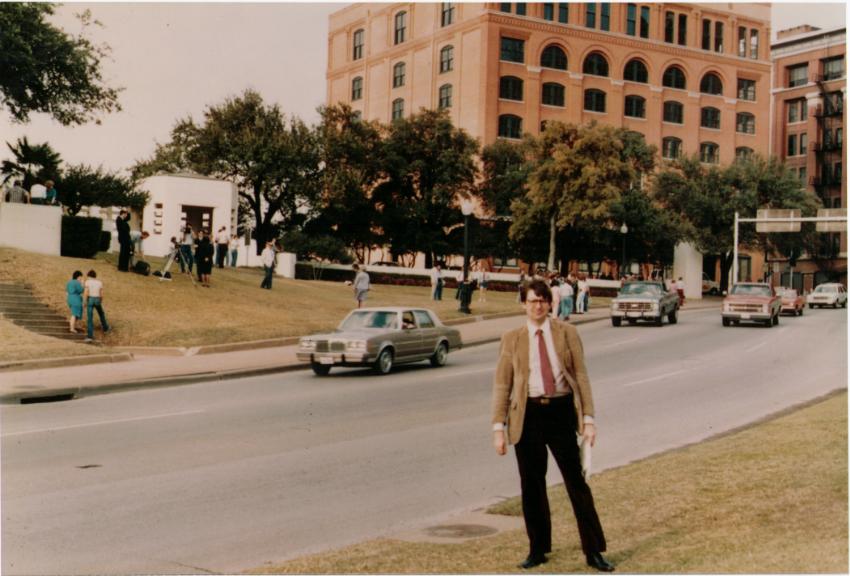

Joseph McBride Speaking in at the Coalition on Political Assassinations - Youtube Video - Click Here to Play

Joseph McBride in Dealey Plaza, Dallas Texas

Don't Stop Dancing

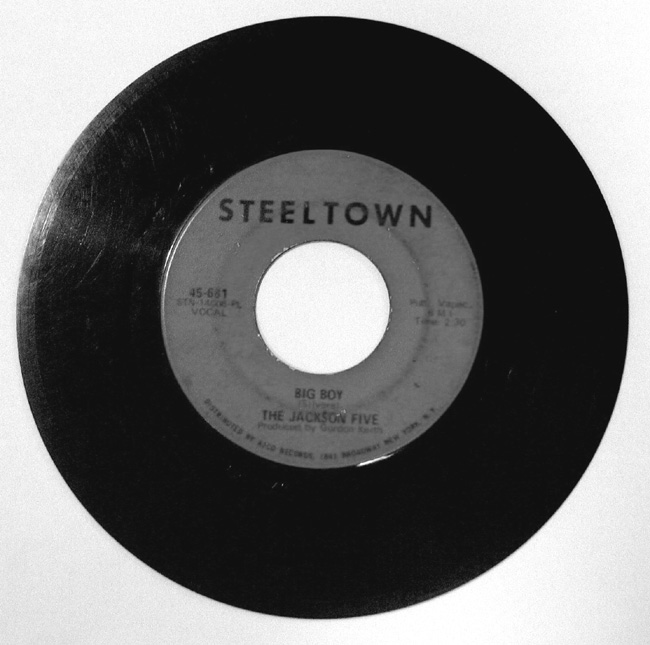

Based on the Investigation of the Life/Music/Career of Michael Jackson

Neverland

More about the movie, Don't Stop Dancing CLICK HERE.

Big Boy

Let us not seek the Republican answer or the Democratic answer, but the right answer. Let us not seek to fix the blame for the past. Let us accept our own responsibility for the future.

John F. Kennedy

JFK HEADSHOT - CLEARLY FROM THE RIGHT FRONT

Zorro: The Unveiling of the Killing of King by Patrick Wood brings the hidden details of the 1977 Gary Revel investigation of the assassination of Martin Luther King JR. to light. He is writing and publishing the story in chapters in a way that brings to life the intimacy of Gary's dangerous quest of finding the truth and more. To begin your own personal journey Click Here to Read.

MLK Assassination Investigation Links

Copies of pages from the transcript of the James Earl Ray guitly plea hearing and analysis by Special Investigator Gary Revel

Dark Arts of Assassination by Patrick Wood

Investigating the Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. - People get Killed

J Edgar Hoover's FBI Destroy King Squad

Investigating the Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. - People get Killed

Leutrell Osborne Finds Disturbing New Details Investigating Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination

MLK Conspiracy Trial-Transcript

Mystery Helicopter and Riot Control in Memphis During March with MLK

New Questions About E. Howard Hunt And MLK Assassination-A Gary Revel Commentary

Pictures of Assassins

The Case Against James Earl Ray: Anyalysis by Martin Hay

The Deadly Business of the Murder of Martin Luther King Jr.

They Slew the Dreamer - Lyrics and History

More Assassination Research Links

3 Tramps in Dealy Plaza: What are they to JFK killing

Adam Gorightly Interview by Investigative Journalist Bob Wilson

Abraham Bolden-Book Review-Echo From Dealey Plaza

Anti-Castro Cuban exile, Antonio Veciana met with CIA Handler and Oswald

Badgeman: Do you see him and did he kill JFK?

Beverly Oliver Interview-Eyes Wide Shut

Christopher Dodd and the MLK/JFK Assassinations

Bob Wilson Interview with Mort Sahl

Carlos Marcello's Hideout in Swamp by Gary Revel

Chief Curry, the FBI and Assassination of JFK

Conspired to Kill: Opinion by Gary Revel

Deep Throat Surfaces - Watergate and Assassinations

Was Demohrenschildt CIA and Part of JFK Assassination Team?

Download PDF of the CIA's FAMILY JEWELS - FREE

Interview of Gary Revel on guilt/innocence of Lee Harvey Oswald

Interview of Joseph Mcbride

Interview of Joan Mellen

Into the Nightmare-Mcbride Book Review

Gayle Nix Interview-JFK Assassination

JFK and RFK: The Plots that Killed Them, The Patsies that Didnít by James Fetzer

JFK: Antonio Veciana and Lee Harvey Oswald and the CIA

JFK: Antonio Veciana's book, 'Trained to Kill' more evidence of CIA involvement of JFK assassination.

JFK Assassination Bullet Fragment Analysis Proves Second Shooter

JFK Assassination Film

by Orville Nix with interview where he says the shot came

from the fence not the Texas Book Depository.

JFK Assassination Invetigation Continues

JFK: In The Light of Day by Gary Revel

JFK: In The Light of Day Update by Gary Revel

JFK: Robert Kennedy-Rollingstone Article

JFK: The Real Story-Movie Project

JFK: Through the Looking Glass Darkly

JFK: Why and How the CIA Helped Kill Him

Mikhail Kryzhanovsky tells it like it is.

Officer of the Year: Roger Craig, Dallas Policeman and Mystery Witness of JFK Killing

Russo, Oswald, Ferrie and Shaw

Shane O'Sullivan Interview

John Whitten: How the CIA Helped Kill JFK and Keep Their Guilt Hidden

Judd Apatow tweets his displeasure with theaters delaying opening of THE INTERVIEW (movie about a CIA plan to assassinate North Korea's Kim Jung Un) due to the GOP's terrorist threats.

RED POLKA DOT DRESS: Movie project, the mystery of the assassination of Senator/Presidential Candidate Robert F. Kennedy; screenplay by Frank Burmaster and Gary Revel.

The business of murder related to Santo Trafficante, the Mafia, the CIA, JFK, MLK and RFK

The Girl on the Stairs says Oswald did not pass her after the shooting of JFK

The Mystery of Roger Craig and the JFK Assassination

How the CIA Kept Secrets From the HSCA

Why and How the CIA Helped Assassinate JFK

John Lennon Assassination

A Not So Funny Thing Happened: (WHILE LOOKING INTO THE MURDER OF AN EX- BEATLE)

John Lennon and ...

John Lennon killing, Wanna be a hero?

More Interesting News-Commentary-Perspective from Gary

Deep Throat Surfaces - Watergate and Assassinations'SOMEONE IS HIDING SOMETHING' by Richard Belzer, David Wayne and George Noory.

Is the disappearance of a commercial airliner with over 200 people on board no more important than a fender bender? This book draws a staggering conclusion that some may want us to believe this airline tragedy isn't even that important.

Photos, pictures, art, books, poetry, news, and more at the Gary Revel PINTEREST Website.

Embrace ... Concept Art by Gary, Canvass, Posters, Prints ... on sale at Zazzle-Click Here

Gary Revel found links to those responsible for the assassinations of JFK, MLK, RFK, John Lennon and the attempted killing of President Ronald Reagan.

Owner of Jongleur Music Group of companies that includes music publishing/production/distribution, movie development, and book publishing.

https://garyrevel.com

Email: gary@garyrevel.com

Website Copyright 2006-2019 by Gary Revel